New York/New Jersey VA Health Care Network

Kazuo Yamaguchi A National Salute Story

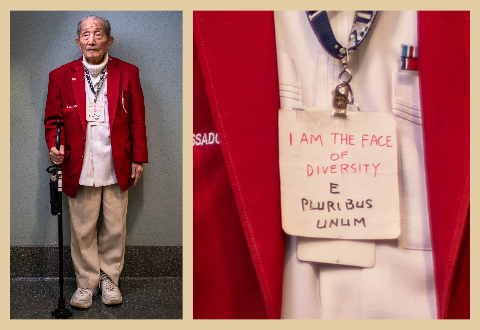

Mr. Kazuo Yamaguchi

Coming of age in 1930s Queens, N.Y. — while America rallied out of the Great Depression and inched closer to a second World War — can make for a very unusual life. Especially when you're rich.

“All of my friends growing up were mafia. My best friend was consigliere to John Gotti, and his father was consigliere to Vito Genovese. I wasn't the average kid. My grandfather was a millionaire. I grew up like a prince.”

For the wealthy, mafia-adjacent teenager living in the shadow of the war now raging in Europe, life was as normal as it could be – until Japan launched an attack on Pearl Harbor, forcing America into the conflict.

Young Americans, from a multitude of varying backgrounds and economic stations, clamored to join the U.S. military during that time. Upon graduating from Ozone Park's John Adams High School, Kazuo Yamaguchi — a kid from Queens who grew up like a prince — felt the call to serve the country that had provided a fruitful life for him and his family.

“My father said to me, 'Kazuo, our country, the United States, has been good to us,'” remembered Yamaguchi, as his father laid out the concepts of on, or duty, and giri, or honor for him. “'Look at your grandfather, the successful business he was able to build for us. America has done wonderful things for us.'”

However, the attack on Pearl Harbor pointed widespread suspicion toward Japanese-Americans and tt wasn’t until he was turned away at the recruiting station that Yamaguchi fully began to realize he was not just another kid from Queens. As a second-generation Japanese-American – a nisei – Yamaguchi was rejected by the U.S. Army over concerns of potential allegiances to a foreign government.

“I did try to join,” said Yamaguchi. “But, then I found out that they weren't interested. I'm a 'Jap.'”

Rejected by his nation, Yamaguchi went on to study agriculture at the University of Connecticut. But, not even a year into his schooling, he was suddenly drafted into service and sent to Camp Upton, N.Y. for basic combat training.

“They needed me. But, they didn't trust me,” said Yamaguchi. “Wherever I was assigned, they wanted to see my identification card.”

Upon arrival, Yamaguchi was immediately assigned to a segregated unit for Japanese-Americans. There, he trained to defeat the enemy – an enemy who looked just like him and who looked like the more than 1,000 New York-based Japanese-Americans who were imprisoned in the internment camp at Camp Upton.

“The majority of us went to Army infantry. The rest of us, they wanted us for the Military Intelligence Service,” said Yamaguchi.” “They found out that I was bilingual and knew about Japanese culture. They said, 'No, Yamaguchi. You're not going infantry. You're going intelligence.'”

Despite being born and raised in the United States and successfully completing both basic combat training and advanced intelligence training, Yamaguchi was still under intense scrutiny due to his heritage. No matter what he or his fellow countrymen did, their identity as Americans was being challenged by the very country they were defending, and their loyalty was being questioned by the service that drafted them.

“When I deployed to the Philippines, we shipped out of Minneapolis on a train, and anytime we passed through a heavily populated area they made us pull the shades down,” he remembered. “I asked if they were ashamed to show that these Japanese faces are in the Army. I pulled my shade up.”

Even aboard his troop ship as steamed toward the Philippines, Yamguchi and the other Japanese-American soldiers continued to suffer the effects of racial tensions. They were segregated from their fellow service members and they were mistreated to the point where they had to draw their weapons in self defense after the other soldiers turned a sea hose on them.

“[Someone] called the military police. They came with their .45-caliber pistols. We pulled our M1 Garands,” Yamaguchi recalled.

Racial tensions were not the only problem aboard the ship. The troop carrier was held up in Tokyo Bay by a flotilla of deadly mines. Yet, even with their five-inch cannons, the ship's gunners were unable to clear a path. It was in this moment that Yamaguchi and his fellow Japanese-Americans rose to meet the challenge. Using only their rifles, they were able to clear a path ahead and earn the respect of the entire unit.

“We were good. We didn't pull any punches,” he added. “No matter where we went with them, we let them know it.”

By the time Yamaguchi's ship reached Japanese soil, America had dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, forcing the country’s unconditional surrender. As his unit continued toward Tokyo to begin their work as interrogators and interpreters, Yamaguchi performed his duties with a heavy heart.

“My only interest was to get in without killing everybody and to tell them that we are here to be translators for the Americans so we could rebuild the country,” said Yamaguchi.

Yamaguchi arrived in Tokyo, believing it was his responsibility to help heal the unimaginable devastation caused by his country's recent actions. Japan had surrendered. He was no longer an enemy combatant, and he wanted the locals to understand that.

“There were Japanese people who hated us. They'd say, 'You're ethnically Japanese. Your parents are from Japan. You're in an American uniform as MIS---what're you doing here? You're a traitor,'” Yamaguchi recalled.

Nowhere was this divide between his ancestry and his country more readily apparent than when riding on Tokyo’s train system. Yamaguchi was ethnically Japanese, but he was still just a kid from Queens. He was still in a segregated car. But, this time, he was in the car for Americans.

Yamaguchi desperately wanted to learn more about the people he was trying to help. But, the social divisions present in that situation made it nearly impossible. So, in an effort to bridge those divisions, Yamaguchi intentionally boarded the wrong train car and inserted himself into Japanese society.

“Right after the surrender, I'm on a train and I see a Japanese veteran in his robe. He sees me in his car, and not in the occupation car, and he screams, 'Roosevelt's spy!' I wondered what was going to happen,” said Yamaguchi.

If he was to become a helping hand to the people of Japan, he had to change his surroundings. Yamaguchi apologized for what happened during the war and, in conversation, found that they shared very similar values.

The lessons Yamaguchi learned from his family – duty, honor, and an appreciation for his heritage as a Japanese-American – helped him find the middle ground between himself, a Japanese-American soldier, and the people of Tokyo.

“I was appreciative of what my parents and grandparents taught me about Japan and Japanese culture. I felt that the Japanese people needed me because I understood their hearts, and I knew the terrible things we did to them. They were barely surviving, and it was my responsibility to do everything that I could to help them,” Yamaguchi said.

Aboard that train, Yamaguchi made it a point to emphasize that he was just another person who wanted to help. American and Japanese soldiers were no longer enemies. The war was over and they now had a shared goal in helping each other to rebuild the country.

“I am not gaijin,” Yamaguchi told the veteran. “I understand duty and honor.”

As soldiers, Yamaguchi and the veteran saw duty and honor as values that they were to live and die by. However, his obligation to respect these values would eventually put him in difficult situations; Yamaguchi was sometimes torn between his duty to help people and the orders given to him from higher ranking officials.

“All of us nisei, we saw these kids around dying of starvation---they were orphans. We couldn't allow that. We bathed them, we fed them, we cut up our spare uniforms and clothed them. These kids had post-traumatic stress disorder, they saw what we did to their parents,” said Yamaguchi.

An officer in charge of Yamaguchi and other Japanese-American soldiers gathered them all together and gave notice that they were not to give aid and comfort to the enemy. Forced to choose between his duties as a soldier and the values instilled in him by his family, Yamaguchi did not hesitate.

“He had a white guard posted in front of the chow hall to inspect us so that we didn't take out extra food for the kids. We told the military policeman, 'Do you want us to get our M1s?” Yamaguchi said. “We embarrassed him. When the commanders heard what was happening, he got demoted. It felt good to save those kids.”

Even after separating from service, Yamaguchi continued to develop his vision of defending basic humanity and fighting for an individual’s right to live with dignity. The Congressional Gold Medal recipient and member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team – the most highly decorated unit in U.S. military history – continues to fight in the name of dignity, and to teach the importance of recognizing our shared humanity to his fellow veterans.

Yamaguchi, now 94 years old, drives himself from New Jersey to the Northport VA Medical Center once every week to volunteer.

“My responsibility is to teach these young veterans something very important,” Yamaguchi said. “I want to teach these young veterans to care. Caring sounds simple but, no, to care is very deep. That feeling of caring comes from the heart... I try to keep race out of it, it has nothing to do with race. It has everything to do with being a human being. That's my responsibility.”